Toronto is currently undergoing a tumultuous debate about the future of its transit network. Council has debated, approved, and reviewed decisions on Transit City, One City, the Scarborough subway and soon SmartTrack.

Torontonians are justifiably frustrated by the challenge of moving forward and believe that out process of transit planning is broken. We feel as if we are falling behind.

Reading Robert Fogelson’s amazing chapter on Derailing the Subways in his book “Downtown: It’s Rise and Fall, 1880-1950,” I was struck out how much the challenges of modern day transit building mirror those of the past.

We have an image that subway building was extremely productive in the early 20th century in North America. But unlike large European cities, very few North America cities invested in a rapid transit network, when downtown reigned supreme and urban densities were at their peak. As Fogelson writes:

“by the late 1920s, after more than two decades of vigorous efforts, after the preparation of scores of studies and reports, after the expenditure of millions of dollars, and after a host of predictions that most big cities would soon build a rapid transit system, nearly 90 percent of the els, close to half of which had gone up before the turn of the century, were in New York and Chicago. And more than 90 percent of the subways were in New York and Boston, both of which had begun to build their first underground lines before 1900.”

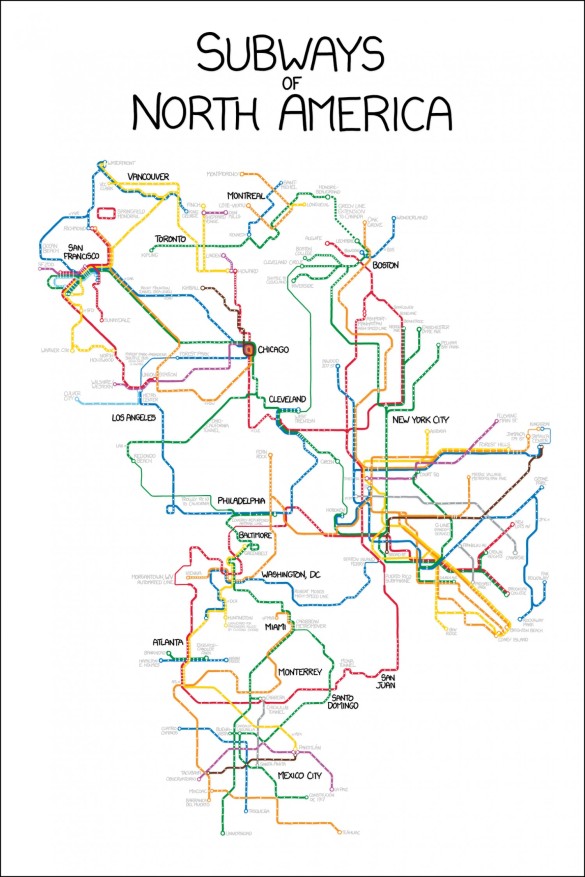

The map above really demonstrates how mass transit in North America is concentrated in just a few cities. Over a dozen cities studied building transit in the early 20th century, including Toronto, yet very few did.

Why? One reason was that subway advocates were strongly divided over the question of why, where, and how to build subways. Was it relieve traffic congestion or promote residential dispersion? Should the system be built incrementally or all at once? How should cities pay for the transit? By taxpayers, property taxes, or special assessments? Why should only downtown benefit from subways, while other parts of the city would not benefit from the investment?

The issue of how to pay for subways was significant. The costs involved were astronomical even then, when compared to streetcars and elevated rail networks. Very few cities had the revenue tools, or desire to pour so much capital into subways, especially cities that lacked the density of New York, Boston, and Chicago.

There was also a significant cultural shift in the early 20th century. The ultimate solution to traffic congestion in North America was not to improve and invest in rapid transit but to spread the city. There was a powerful idea that the “cure” to congestion was to decentralize. Contemporaries looked to New York and believed subways only make congestion worse by funnelling people into a dense core.

But Los Angeles points a way forward for cities like Toronto. Los Angeles tried to build a decentralized metropolis, it didn’t work.

In the 1990s, Los Angeles began the subway project it abandoned 70 years before. In 2008, Los Angeles residents approved a 30-year, 0.5-per cent regional sales tax that pour $40 billion into transportation projects. Currently the City has six major transit projects underway including a subway line, four light rail lines, and a bus rapid transit way.

If there is one thing that history can tell us it is that mass transit was never an easy sell in North America. It takes considerable investment, long-term planning, and commitment across city regions. Hopefully, our 21st century efforts, led by Los Angeles and hopefully Toronto, will be better than those at the beginning of the last century.