Recently, Alberto Hernando de Castro, a physicist with the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Paris, and his colleagues wrote a paper reporting to have found two simple rules that explain how cities grow.

Hernando, after examining the growth of 8,100 Spanish cities, proposed that the future growth of a city depends on how the city grew in the past and that the growth of a city depends on the growth rates of neighbouring cities.

The Cities Centre at the University of Toronto released a report by Jim Simmons and Larry S. Bourne this summer, “The Canadian Urban System in 2011: Looking Back and Projecting Forward.” The report manages to provide similar insights, which suggests that there may be a degree of universality to Hernando’s two rules.

In regards to the first rule, that how a city will grow in the future depends on how it grew in the past, seems consistent with the Canadian context. Despite all the changes that have swept Canada in the last 100 years, the way Canadian cities have grown has been remarkably steady with only a few changes in the urban hierarchy in the last 100 years.

Of course there are differences between now and 100 years ago, the most obvious being that Toronto is now the dominate Canadian city. One hundred years ago it was Montreal. This is because the rule has about a 15 year lifespan. Hernando found that cities in Spain have, on average, a “memory” of 15 years, meaning that 15 years of past growth can reliable help predict the outline of the next 15 years of growth.

I’m curious about what is the “memory” of Canadian cities. With fewer and younger cities I suspect the cities “memory” is longer. The biggest cities have been growing relatively consistently over the last 30 years and tend to dominate their regions, which is related to the second rule.

The second rule that “cities within about 50 miles of each other are entangled… so that if one of them grows, the other also grows in the same proportion” also plays out in Canada.

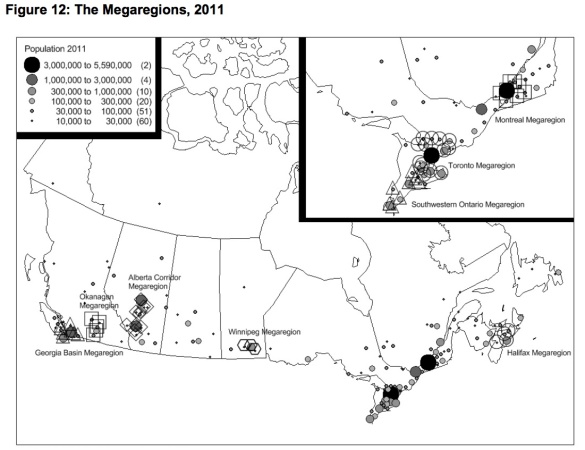

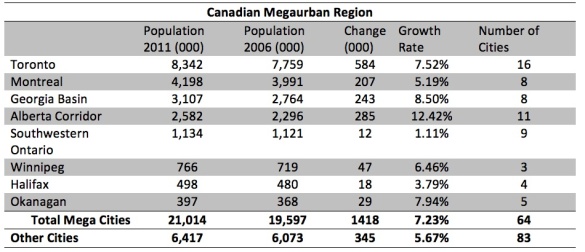

Simmons and Bourne call the observed entanglement “Megaurban Regions.” They identify eight Canadian Megaurban regions where roughly 64 cities and 21 million people are entangled. Within those eight regions cities and population tend to grow at similar rates.

Simmons and Bourne argue that primary driver of growth in each Megaurban region is dependent on the size and rate of expansion of the market in which the metropolitan region is embedded.

For example, Halifax is limited by the slow growth within the Atlantic region and Montreal is hampered by the slow growth within Quebec.

Toronto, on the other hand, is not limited to Ontario’s market but embedded in the national market, a role formerly held by Montreal. Because Toronto region is so large it also attracts much of the investment in Ontario.

As a result, smaller cities and regions in the Province, such as Kingston and Southwestern Ontario region, are growing far slower. My previous post on the Southern Ontario’s Geography of Innovation, touches on this theme as well. Many smaller Southern Ontario cities are trying to deepen their “entanglement” with Toronto through improved rail service (Note: In my post I’m using a different definition of Southern Ontario than Bourne and Simmons) .

I would be interested to see Hernando’s computer model applied to Canada and see how well it meshes with Simmons and Bourne’s analysis. What are the unique Canadian twists to a global model of cities? Or are Canadian cities, and all cities, merely following some basic global rules?